The Original X-Men: Mutants Before the Metaphor

Merry Mutant Review

Marvel’s Merry Mutants

The Silver Age of comic books was picking up steam in the latter half of 1963. With the immense success from Fantastic Four, Spider-Man and other recent creations, Marvel was looking to add titles to their roster. Establishing a universe and core audience for their comics was seemingly at the forefront of the company’s minds. With perhaps a bit of a peak over at DC’s Doom Patrol, Kirby and Lee debuted the X-Men, a team of the ‘strangest’ superheroes of all. However a glance at the group would not necessarily back up the claim.

Looking at the new teen team, there’s not a lot of strangeness on the surface. Four teen white boys, with identical hairstyles of varying shades of blonde and brown, alongside one red headed teen girl isn’t exactly a circus act. However the makeup of the team showcases two major points for the series. First, the idea of secretly being different, of not outwardly displaying differences is a distinct theme for this era of X-Men. This is in slight contention with the development of the idea of the mutant metaphor in the ensuing many years, but that has not taken hold yet. The second implication of the included roster is a bit simpler, it’s just demographics.

Marvel as a company tends to be comics made by and for young white guys, often not for the better. The modern understanding is that the X-Men’s mutant metaphor is applicable to various oppressed groups, but that’s not really the case in 1963. The goal of this team seems to be much more for young boys to project themselves and their friends onto the teen superheroes, and their related drama. The series is not a progressive social commentary at this point, if it ever truly is.

Understanding the approach of the creator’s at this point is essential in enjoying these classic comics with the current and long running context of the X-Men. The story is light, the plots are relatively simple, and the character’s are consistently inconsistent. This has to be taken in stride with a story over 60 years old, and under the surface there are actually more persisting elements in the first nineteen issues than it may seem.

Meet the Original Five

Warren Worthington the Third, aka The Angel

Blonde haired, with white feathery wings, Warren Worthington is exactly what’s expected from someone with his codename. Besides being a bit of an overconfident rich boy, there’s not too much depth to the Angel. He spends about half his time dodging airborne projectiles, and the other half hitting on his younger teammate Jean Grey. The unfortunate side for Warren is that his haughty advances mostly serve as a foil to the reserved Scott Summers, and his own pursuit of Jean. Warren’s passes often result in Jean’s admonishment, and her thoughts indicate she is much more interested in Scott.

He’ll be more fleshed out and overly complicated down the road, though he won’t ever completely shake his womanizing behaviors. The flying X-Men comes out a bit boring in the debut run, but is certainly fun to see swoop around when drawn by Jack Kirby.

Hank McCoy, aka The Beast

Everyone’s favorite bouncing blue beast makes his start in a decidedly paler than expected fashion. The transformation of Hank into the hairy version of himself is so iconic across other media, it is a stark realization that the character does not begin with this in mind. Besides his outward appearance though, it is remarkable how much of Beast’s personality is already shaping up in the Silver Age.

A central point of Hank’s character is that his brain is as useful, if not moreso, than his mutation. Whether he looks like a regular teen, ape, or cat monster, he keeps the mind of a genius. Even as a normal looking guy, Hank is already insecure about others not recognizing this trait. Early on he adopts an overly verbose way of talking, clearly meant to showcase his smarts to those around him. It’s charming to read, but would almost certainly be unbearable in regular conversation. As seen in issue eight however, the way he uses his words may be the least concerning aspect of Hank.

Professor X leaves the team for a short while to battle the elusive Lucifer, after surprisingly graduating the team from the school. This progression, along with a traumatic incident involving an angry mob of humans, pushes Beast to exit the X-Men. The harshness of what happens and the speed at which Beast turns are compelling lines when connected to the long term moral failings that will besiege him. Even when he returns, the methods Hank employs are ramped up in intensity.

Since Unus the Untouchable (a mutant enclosed in a personal force field) easily defeats the X-Men in combat, Hank turns to his brain in an attempt to take down the villain. What he devises is questionable and borderline sinister. He whips up a device that increases Unus’s mutation, extending the force field that covers him further outward. This creates the practical issue of Unus being completely unable to touch anything, and he cannot manage to eat or drink. The X-Men use this as leverage, and tell him that should he ever try to join Magneto they will zap him with the ray again, and force him to die of malnourishment.

It sounds bad for Beast and the others, but to be completely fair Unus is a man trying to murder a bunch of teens so that he can join a madman in conquering the world. Still, with the long term arcs of Beast, and the idea that he always is willing to go a little further than other mutants in order to secure safety is cool to see established so early on.

Bobby Drake, aka Iceman

The youngest of the original five teens, Bobby Drake/Iceman, will face a continued character struggle that is exemplified in his uncreative name. For the vast majority of his publication history the threat of being generic or shallow will haunt the quickly named superhero. A consistent jokester, Bobby often falls into the trap of being just comedic relief in lieu of any personal depth. Arguably that is true even in the genesis of the series, but a couple of creative decisions boost the coolest X-Men up a couple of tiers.

First and largely unimportantly, the costume. Iceman’s costume is essentially just a pair of boots he slides on over his completely snowy exterior. It’s a charming and simple gag that goes with Bobby well. The most interesting aspect of his getup is the frozen layer he manifests for himself.

At the start of the series, Bobby is covered in a layer of fluffy snow. Kirby draws him with lots of curved lines, creating a rounded pile effect that is reminiscent of The Thing with a softer exterior. It’s a distinct look that may be unfamiliar, as it is not the typical look that Bobby will sport for the rest of his career. A bit unceremoniously in issue eight, Cyclops suggests to Iceman that he try and ‘harden’ his snow form into a harder ice material, and he is quickly successful. This quick but lasting development points to major themes for the character, including his vast capacities power wise, and his stark lack of self-awareness.

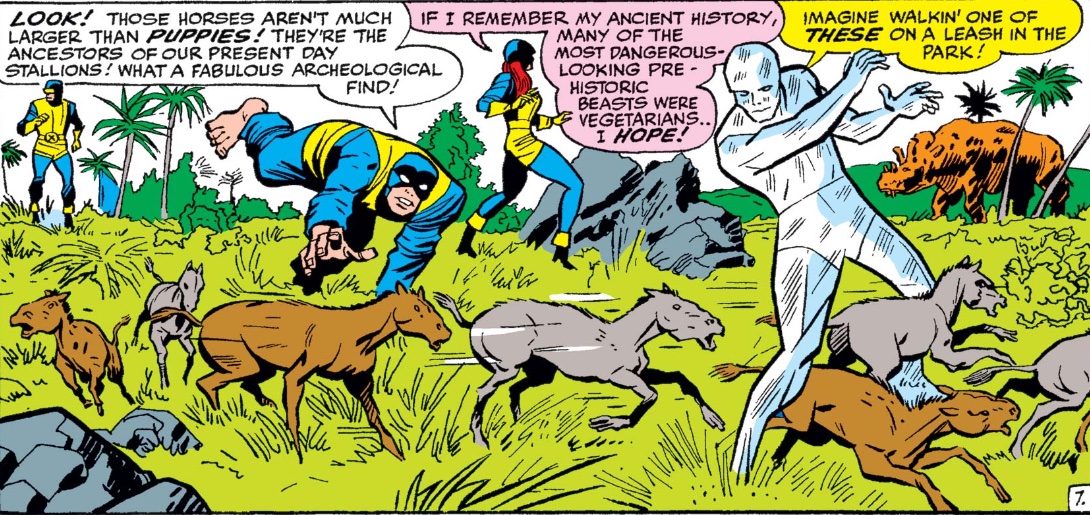

For the duration of the run, Kirby essentially utilizes Bobby’s ice as an artistic outlet and convenient plot device. It’s apparent that Iceman can essentially create anything with his ice, and this intense versatility helps to push the story. From teleportation via water, to revitalizing an entire planet, the throughline of being naively wielding great power will continue to come up. As he gains abilities though he doesn’t always develop personally, which results in a character with too much power and too little motivation. It’s funny that this potential flaw could be due in part to Kirby and Lee simply having fun with their character, and the trend continuing.

Some of Bobby’s displays of strength are done when he himself is not even in control of his body. As outlined by Taylor Lancaster for Screen Rant, when Emma Frost inhabits Bobby’s body in Uncanny X-Men 314 she unlocks levels of the powers that were previously unknown. He’s embarrassed and upset after the realization that she immediately was able to master and utilize his own mutation better than he had any conceived.

This characteristic of lacking self introspection is expanded on by Brian Michael Bendis later on in reference to the character’s sexuality. It is a neat throughline to track, since Iceman will be woefully relegated to a banter-fueled powerhouse of a plot convenience for large stints of his publication.

Scott Summers aka Cyclops

The fourth member of the starting five falls into a similar pattern with the rest of being relatively well established. Though these are dated comics, and in some senses shallow, there is still an undeniable kernel for the character of Cyclops that is already present. Perhaps due to superhero comic’s tendencies to reset characters to their established base, Scott feels firmly on track to fulfill his future roles. Even today when the character has evolved ten times over, there is still a likely chance that any adaptation of the character will mirror the personality seen in these pages.

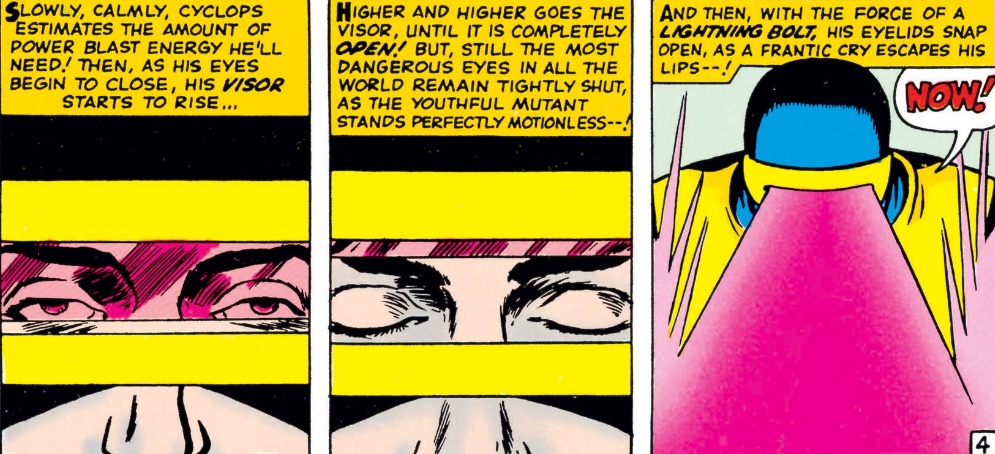

The first highlight of Cyclops is slight, and that is his mutant ability, and in some instances disability. Laser eyes themselves may be one of the most run of the mill power sets, right up there with angel wings. However Scott is unable to control his optic blasts, and that decision from the creators alone adds a lot of complexity to him. Throughout the issues, all of his teammates are ‘mastering’ their mutations and generally expanding their capabilities, but Scott is never able to do this.

Cyclops remains reliant on his glasses or visor lest he unleash destruction. It’s a simple setup, but for fans it works time and again. He has a rollercoaster of a story ahead of him, but the concept of having to be so careful all the time and never truly being in control remains as an undercurrent and terminal anxiety. Ironically being in control is exactly something that Cyclops is known for, again just not of himself.

Many times over Scott will be touted as a ‘natural leader’ and will consistently be handed the reins of the X-Men, at least in the field. On the other hand, the leader role will just as often be stripped from Scott and given to someone with more experience, capabilities, or trust from peers. It’s a mix of character developments and the ever present editorial pull to reset the original five, coming together to create a somber scenario.

When following Scott it adds a lot to know that he will go through so much, and he will ever so slowly change, but eventually he will become fleshed out, with relatable ideals and flaws alike. He has a much more explicit arc in long running comics than a lot of characters, even more so than his preceding teammates.

These issues see the birth of the golden boy, and he does ascend to be the official leader. Of course it is taken from him in the end, and he never is able to match his teammates in mastery and scope of their mutations. Scott Summers has a lot to learn, and his lessons will be much more enjoyable for the reader than to him.

Jean Grey aka Marvel Girl

The last and certainly least well written of the original five is unsurprisingly the only girl on the team, Jean Grey. Pretty and stereotypical, while Jean is initially introduced as almost a viewpoint character for the reader, she is quickly relegated to girl to pine after for each of her boy teammates. Marvel’s overall writing of women is a well known weakness in almost all eras of the company, due in large part to their refusal to hire them to write. Setting the more antiquated bits aside, there is plenty to be appreciated around the growth of Marvel Girl.

Much like her chilly teammate, Jean Grey’s powers will only grow and grow over the years, to the point she will serve as the ultimate plot convenience when written poorly. She will be able to do essentially anything that is needed to move the story, but that is still far in her future. To begin, she can only lift small objects for a short time, though over the course of these issues that drastically changes.

As early as issue six Jean is lifting Hank in the air, demonstrating a marked increase in power since her recruitment. This continues with her establishing a patented technique of defeating the super speedster, Quicksilver, by simply lifting and spinning him in the air. In the tenth issue Jean is able to disassemble and rebuild a rifle, and a couple of issues later she shows that she can lift herself off the ground, in the introductory battle against the Juggernaut.

The seventeenth issue gives the first indication that Jean’s mutant ability is akin to the likes of Magneto, meaning it can essentially do anything. In a rush to return to the mansion, she utilizes her telekinesis powers to run and leap over obstacles for miles, alongside Beast. It’s a unique usage that shows just how versatile being a telekinetic can be. Altogether her gradual growth is another early indicator of later significant developments. Dealing with immense power in all facets, physically, emotionally, morally, etc, will be a massive recurring theme for Jean. Besides her capabilities though, there is little beyond her basic relationships that will define her personality in the long run.

The Mutant Metaphor or Lack Thereof

For the original team, there are plenty of character points that are long running and get their start in the opening run. However the underlying thematic framing of the mutant metaphor is simply not present in the way it will be for the majority of the series. Applying the analogy of mutants to most any oppressed groups doesn’t really work beyond surface examination, and isn’t explored by the narrative.

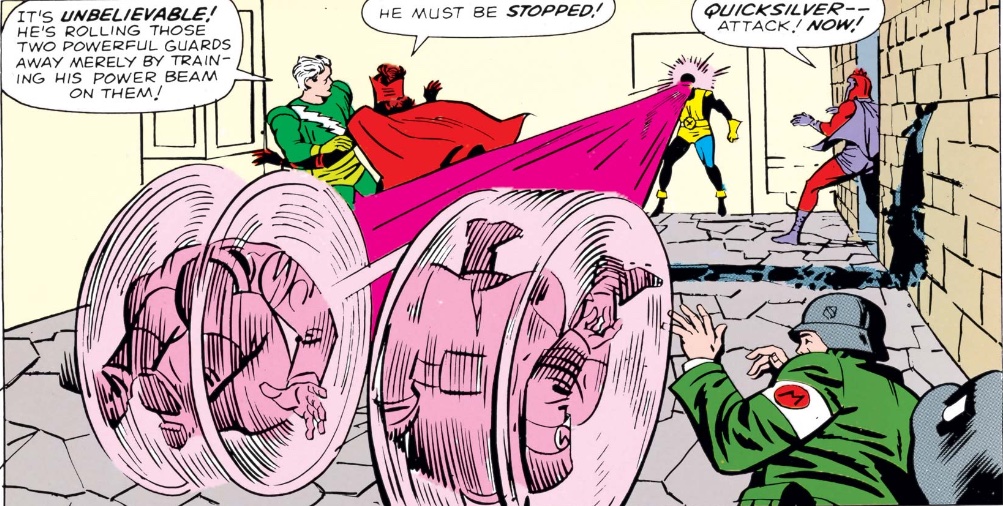

Take for example the famously inaccurate casting of Professor Xavier as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Magneto as Malcolm X. At this point in the series, Magneto is a cartoonish, over the top villain who can only be rationalized as a deeply traumatized person. He does not have a cogent ideology and to relate him to any real world person is simply silly. Xavier and MLK though are a bit more comparable, but far from similar.

In the eyes of the public, Xavier is a non mutant expert on genetics, evolution, and human mutations. He advocates for assimilation and nonviolent compliance from the mutants, so they can integrate into society. MLK obviously never presented as a white man, and openly called for radical change and equality. Xavier is the white moderate, and anyone unaware of MLK’s opinion on the white moderate shouldn’t be.

Community of Freaks

Alongside the lack of metaphor, the story structure itself is distinct from that which will come to define the series. Long running plots, multiple threads weaving through each other, heaps of melodrama, and other staples of the X-Men universe are not seen in these issues. Instead and in line with the times, the stories are mostly self-contained, starting and wrapping up in a single issue or two. Though to say ‘story’ may be a bit of a stretch in some instances.

The experience of the first nineteen issues is not so much a singular narrative experience as it is a wild tour through a wacky corner of a wacky universe. Characters and concepts are introduced quickly and often, making the pace change depending on how thorough of a reader one is. There’s a lot of fluff in the dialogue, but also a lot of wit to make it worth it. At no point does there seem to be a logical endpoint, and through the whole run there is a palpable focus on building out the mutant community and filling its ranks. The universe feels poised to facilitate a much larger ensemble for a longer time than other superhero comics, with more of a focus on community and relationships.

Ironically it will be one of the few canceled comics started by Lee and Kirby a bit down the road, though when it comes back it will double down on pretty much all the melodrama and worldbuilding. It is genuinely impossible to gauge accurately how much of the heart of the X-Men comes from Lee and Kirby directly, or how much their work has inspired other creators on the title. While other authors will completely recontextualize it, these beginning issues lay the foundation for the community of muties that will attract readers for generations.

Y’all Seen This Jack Kirby Fella?

Very little feels as close to reinventing the wheel as analyzing and praising Jack Kirby’s artwork. It’s pure fun, but that’s no revelation. It’s remarkable how characters such as Magneto, Cyclops, Iceman, many of the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants alongside others, are already iconically designed, and won’t have a ton of true changes in their looks for years. It is a bit disappointing and surprising that through all the many mutants introduced, they are consistently just normal looking dudes with powers. The costumes are more striking than any of the physical mutations that are introduced. There is surely some missed potential, given how the mutants will be portrayed later on it would have been interesting to see Kirby’s takes on some really radical looking mutants.

It’s clean, simple, and borderline tells the story itself. Some may feel it’s dated obviously given the limitations at the time, but honestly it holds up really well. The bold art even works pretty well when the comic is read on something as small as a phone. There is a real staying power to Kirby’s drawing that gives the issues lasting worth even in the modern context.

Graduating to Greater Things

They are the X-Men we know, not necessarily the ones we love. With less than twenty issues, Lee and Kirby leave a lot on the table. The heart of the series will captivate readers in masses, but that’s arguably not quite here. What is present is foundational groundwork that continues to influence the X-Men and the Marvel comics universe as a whole. Of course that is to be expected with these two creators, but nonetheless is impressive. While it may not resonate as strongly as it did once, the wit and pace of the story both in art and writing create a timeless good time.

Score: 65/100